A fifth generation Californian, Ched is an activist theologian who has worked in social change and radical discipleship movements for more than 45 years. With a degree in New Testament Studies, he is a popular educator who animates scripture and issues of faith-based peace and justice. He has authored over 100 articles and more than a half-dozen books, including Binding the Strong Man: A Political Reading of Mark’s Story of Jesus; Ambassadors of Reconciliation: A N.T. Theology and Diverse Christian Practices of Restorative Justice and Peacemaking (with Elaine Enns), Our God is Undocumented: Biblical Faith and Immigrant Justice (with Matthew Colwell); Watershed Discipleship: Reinhabiting Bioregional Faith and Practice, and most recently Healing Haunted Histories: A Settler Discipleship of Decolonization (with Elaine Enns, Cascade, 2021). Most of Ched’s articles can be found on this site, and books at bcm-net.org.

A fifth generation Californian, Ched is an activist theologian who has worked in social change and radical discipleship movements for more than 45 years. With a degree in New Testament Studies, he is a popular educator who animates scripture and issues of faith-based peace and justice. He has authored over 100 articles and more than a half-dozen books, including Binding the Strong Man: A Political Reading of Mark’s Story of Jesus; Ambassadors of Reconciliation: A N.T. Theology and Diverse Christian Practices of Restorative Justice and Peacemaking (with Elaine Enns), Our God is Undocumented: Biblical Faith and Immigrant Justice (with Matthew Colwell); Watershed Discipleship: Reinhabiting Bioregional Faith and Practice, and most recently Healing Haunted Histories: A Settler Discipleship of Decolonization (with Elaine Enns, Cascade, 2021). Most of Ched’s articles can be found on this site, and books at bcm-net.org.

Learn more about Ched’s Writing.

Ched has worked with a variety of social justice organizations, including the Pacific Issues Network and the American Friends Service Committee. He is a co-founder of the Word and World School, the Sabbath Economics Collaborative, and the Center and Library for the Bible and Social Justice. He and his partner Elaine Enns, a restorative justice practitioner, live in the Ventura River watershed in southern California and work with Bartimaeus Cooperative Ministries.

Learn more about Bartimaeus Cooperative Ministries.

Ched holds a B.A. in Philosophy from the University of California at Berkeley (1978) and an M.A. in New Testament Studies from the Graduate Theological Union (1984). He serves on the faculty of the Proctor Institute Dale Andrews Freedom Seminary, and has taught at the Saskatoon Theological Union, Memphis Theological Seminary, Fuller Theological Seminary, Claremont School of Theology (1998-99 Fellow in Urban Theology), Canadian Mennonite University, Ecumenical Theological Seminary, United Theological Seminary, the Seminary Consortium on Urban and Pastoral Education, Maryknoll School of Theology, Virginia Theological Seminary, Phillips Theological Seminary, Pacific School of Religion, Toronto School of Theology, Vancouver School of Theology, Churches of Christ Theological College (Australia) and Tamilnadu Theological Seminary (India).

Besides his own writing, Ched works with other authors and publishers as an editor and manuscript evaluator. He has traveled throughout North America and abroad giving seminars and retreats, teaching, preaching and facilitating gatherings. He works with Catholic, Protestant and Anabaptist parishes and diocesan or denominational offices, as well as with ecumenical and interfaith organizations. He supports many faith-based peace and justice efforts including Christian Peacemaker Teams, the Catholic Worker movement, Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice, Creation Justice Ministries, and The Abundant Table Farm Project.

Ched has retired from traveling out of California to speak, but continues to resource gatherings through online videoconferencing. To invite Ched to work with your community please

Ched described his work

Over the decades, I have sought to respond to the discipleship call in a variety of ways: as an activist, writer, community builder and popular educator. It is my conviction that the First World church can only be renewed by rediscovering its witness to God’s dream of the Peaceable Kingdom and justice for all. Historically in the U.S., people of faith have been on the forefront of struggles for social change (in our generation this has included movements for civil rights, labor solidarity, immigrant and refugee rights and disarmament). Today we need to animate a new generation of ecumenical leadership committed both to the gospel and to social change. In the metaphor of Jesus, we must be willing to “address the mountain” of injustice.

I’ve traveled around North America and abroad in pursuit of this vision, moving among a wide cross-section of faith-based groups and parishes teaching, listening, challenging, encouraging and networking. I pursue a holistic pedagogy of “theological animation” that integrates the disciplines of popular education, evangelism, political organizing, pastoring and theological reflection.

At the center of my approach is the practice of relectura: a “rereading” of the Bible in light of concrete struggles against violence and oppression. I believe that the Judeo-Christian sacred story is an older, deeper and wiser tradition that has the power to transform our lives and our history–but only if we can overcome its domestication under the dominant culture. Our churches – conservative and liberal alike – are often inhospitable to the gospel’s invitation to the cross, to solidarity with the least, and to Sabbath Economics. Our task is thus to rebuild literacy in which the Word and the world are brought to bear on each other at every turn.

When and wherever this has happened throughout the history of the church, communities of discipleship, creative celebration, healing and solidarity with the marginalized have been created or re-created. The same holds true for our time. I have heard from participants countless times exclamations such as these:

”I’ve been waiting my whole life to encounter this gospel!”

“I’ve long suspected there was more in that text than I was being told!”

Such responses express at once both frustration and hope, and indicate how hungry our people are for an integrative approach to faith and politics.

My work has three goals:

- To recover the vocation of evangelism grounded in Jesus’ call to radical discipleship, engaging communities of faith across the ecumenical spectrum in critical conversation about the shape of discipleship today.

- To help rebuild a movement of faith-based witness for peace and justice by supporting, encouraging and interconnecting diverse local, regional and national expressions of faith and action.

- To promote and nurture biblical literacy and social analysis among Christians by helping groups re-ground their perspectives in sacred stories and discern how those visions can be embodied in our contemporary contexts.

Why “Theological Animation”?

People often chuckle when I describe my work as “theological animation.” Apparently this is seen as a contradictory rubric: the serious endeavor of theology is perceived to have little in common with something as fun-loving as animated cartoons. This, of course, is part of the problem. So I use the double entendre of “animation” intentionally. As I’ve explained above, one meaning is to facilitate a “coming to life.” Here’s the other meaning.

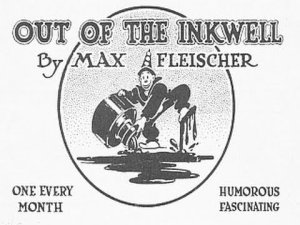

One of the cultural founts from which I draw inspiration is early American animation. Years ago my brother Grob turned me on to the work of cartoonist Max Fleischer, whose animated short features pre-dated (and profoundly influenced) Walt Disney. I am particularly drawn to Fleischer’s “Out of the Inkwell” series. There were two very cool things about Fleischer’s pioneering animated filmmaking.

For one, his cartoons rolled to jazz music–at a time jazz was still very much edgy, underground, and racially segregated (the first African Americans to appear on the silver screen were in Fleischer’s musical shorts). Jazz’s manic, free music cohered perfectly with Fleischer’s rubbery, weird Vaudevillesque cartoon characters (especially Koko the Clown, pictured right). Jazz also fit with Fleischer’s non-agonistic, non-linear stories. That is, there were no good guys or bad guys, and no plot crises in this fabulated toon-world; just characters bumping along to the music, doing random things and having a good old time. Theologically speaking, then, this early art form represented a sort of utopian dreaming, the imagining of a world in which characters never die or suffer, but do a lot of laughing and dancing. (Fleischer invented the time-honored cartoon convention in which characters bounce right up from any and all toon-mayhem.) A vision, in other words, of heaven.

For one, his cartoons rolled to jazz music–at a time jazz was still very much edgy, underground, and racially segregated (the first African Americans to appear on the silver screen were in Fleischer’s musical shorts). Jazz’s manic, free music cohered perfectly with Fleischer’s rubbery, weird Vaudevillesque cartoon characters (especially Koko the Clown, pictured right). Jazz also fit with Fleischer’s non-agonistic, non-linear stories. That is, there were no good guys or bad guys, and no plot crises in this fabulated toon-world; just characters bumping along to the music, doing random things and having a good old time. Theologically speaking, then, this early art form represented a sort of utopian dreaming, the imagining of a world in which characters never die or suffer, but do a lot of laughing and dancing. (Fleischer invented the time-honored cartoon convention in which characters bounce right up from any and all toon-mayhem.) A vision, in other words, of heaven.

No accident perhaps that Fleischer and many of his colleagues were Jewish immigrants: they were, like most of the jazz players to which they were drawn, brilliant artists marginalized by racial-ethnic codes. I think of their early cartoons as a sort of midrash on America, reflecting a longing for life-after-transfiguration: all good.

Any theology that loses sight of that sort of mystical vision of the world-as-it-should-be cannot hope to struggle for redemption in the all too real world-as-it-is, a world that could not be further from a Fleischer cartoon. And that’s why I strive to practice theological animation.