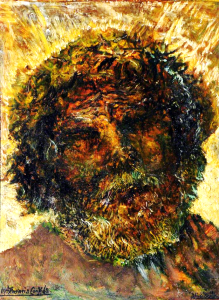

Note: This is an edited version of a homily given at Farm Church on Oct 21, 2018. Right: Francis Ferdinand Maurice Cook, “Head of an Apostle (Blind Bartimaeus),” 1962 (https://artuk.org/).

2018. Right: Francis Ferdinand Maurice Cook, “Head of an Apostle (Blind Bartimaeus),” 1962 (https://artuk.org/).

We have, from time to time, used the sermon time of our Farm Church gatherings to learn more about one of us, in the spirit of “biography as theology.” I’ve had the pleasure of interviewing several of you for this. Today it’s my turn, for two reasons.

One is that this month is the 30th anniversary of the publication of my first book. Binding the Strong Man was/is a commentary on Mark’s gospel—long before political readings of the Bible were cool. I feel gratified to have helped pioneer what is now an expansive field in biblical studies called “imperial-critical studies.” The commentary has had a good run, and is still widely used in seminaries and by preachers, especially during Lectionary Year B. Countless people have told me it has changed their perspective and deepened their faith.

I’m passing around my original hardback copy, beat up and falling apart. And then a copy of the 20th anniversary edition that Orbis Books published in 2008. Elaine and I enjoyed a whole weekend of events back then at Duke Chapel in N.C., with guests and parties that rivaled the shindig we threw at the Maryknoll Father’s pad in South L.A. when the book first came out. This time around, well, we were going to do a little celebration next month down in L.A. with old friends with whom I did Bible studies back in the late 80s. But with Elaine’s recovery we’ve cut back on a bunch of stuff. So we thought at least it might be nice to mark the anniversary today at Farm Church.

The second reason for this awkward exercise in focusing on one’s self (at least for an Enneagram 5) is that the gospel lectionary text for this service is Mk 10:46-52—the story of Bartimaeus. This story—in which Mark gives us an archetypal portrait of healing as a journey from denial to discipleship—has shaped my life profoundly. It was the subject of the very first article I ever published (“Vision from a Blind Man,” Sojourners, March 1980). And what this tale has taught me over the years is this: that embracing Jesus’ call is not a matter of cognitive assent, nor of churchly habits, nor of liturgical or theological sophistication, nor doctrinal correctness, nor of religious piety, nor any of the other poor substitutes that we Christians have conjured through the ages. Rather, discipleship is at its core a matter of whether or not we really want to see. To see our weary world as it truly is, without denial and delusion: the inconvenient truths about economic disparity and racial oppression and ecological destruction and war without end. And to see our beautiful world as it truly could be, free of despair or distraction: the divine dream of enough for all and beloved community and restored creation and the peaceable kingdom. Discipleship invites us to apprehend life in its deepest trauma and its greatest ecstasy, in order that we might live into God’s vision of the pain and the promise.

Forty years ago I was living in an intentional community in Berkeley, CA which had adopted the name of this blind beggar. This was the place where I was midwifed into my life’s work. It was, in retrospect, a wisdom beyond our years that led us to embrace the name of this obscure biblical character. Somehow we knew that we were part of an old, wise story which, as Quakers say, “spoke to our condition.” We intuited that our relative privilege and affluence as First World Christians could not mask our spiritual poverty. So we, like Bartimaeus, desired above all to shed our blindness in order to see and follow.

It was a goofy name for a community. No one could spell it, and we were constantly getting mail to Barnabas, or Bartholemew, and even once to “Bottom-Ass” Community. For ten years we did extraordinary ministry in the name of the poor man. Up to 25 adults and children lived in four households in a working class African American neighborhood. We practiced intensive urban gardening and animal husbandry; maintained a wider local worshipping congregation of some 60 persons; participated in resistance to the arms race and supported the early Sanctuary movement; and educated on radical discipleship and church renewal. And we had some great Halloween parties.

Our community disbanded after a remarkable run, and the clan scattered. But most have continued to follow the Way. You’ve met a few of them at our Bartimaeus Institutes, such as Clancy and Marcia Dunigan. One you haven’t met is Amber Baker. She’s now in her late 30s, farming with her partner Jason at Red Truck Farm in southern Washington, after having worked on farm-worker justice issues and with inner city youth from Portland. Amber was born in our community, and told me once that “there is a part of myself that only surfaces when I am with Bartimaeus people. And I’ve never found anything like it.” I recall a conversation over dinner that Elaine and I had with her some 20 years ago, when she was a young adult on a summer sojourn at the Los Angeles Catholic Worker. We were so impressed with her deep grasp of important things, and asked her where she thought her convictions had come from. “The community, of course” she retorted with some exasperation. “But Amber,” I said, “you were only 6 years old when our community disbanded!” She put down her fork and looked me in the eye with great seriousness. “I remember everything,” she said. And now she’s doing such great work. That’s the power of a community of conviction.

The great Baptist radical Clarence Jordan famously defined faith as “betting your life on unseen realities.” I have bet my life on Bartimaeus; it’s my story and I’m stickin’ to it (as the name of our Coop-erative attests). And speaking of BCM, there’s one other decade anniversary to mention: twenty years ago this fall Elaine and I first met Shady Hakim at a Christian Peacemaker Team gathering in Indiana. Shortly after that Shady began working with us at BCM, and today he is the chair of our board. So it is fitting that today we are also celebrating a house blessing for Shady and Erin here in Ventura.

There’s lots to celebrate today on this Feast of the Blind Beggar: a new home, an old tome, and above all, the power of a sacred story. The Bartimaeus tale for me embodies the power named by Leslie Marmon Silko in her acclaimed book Ceremony:

I will tell you something about stories,

[he said]

They aren’t just entertainment.

Don’t be fooled.

They are all we have, you see,

all we have to fight off

illness and death.

You don’t have anything

if you don’t have the stories.

Their evil is mighty

but it can’t stand up to our stories.

So they try to destroy the stories

let the stories be confused or forgotten.

They would like that

They would be happy

Because we would be defenseless then.

He rubbed his belly.

I keep them here

[he said]

Here, put your hand on it

See, it is moving.

There is life here

for the people.

One thought on ““The Feast of Bartimaeus: Celebrating an Old Tome, a New Home, and a Sacred Story,” by Ched Myers”